My enthusiasm for the subject of art withered during art classes at a public high school in England. It took years to reinvigorate it. Now that I'm a homeschool dad, I think quite a lot about how to avoid smothering the budding passions of my children. In fact, I want to nurture my budding historians!

For example, history is my seven-year-old’s love. I want to open every door for her expansive curiosity. With museums and home education groups closed, I’m getting creative with these history-boosters to encourage my budding historian.

1. Invite Another Enthusiast Over

On a walk with a church friend, I noticed he had a keen understanding of ancient Mesopotamia. Not his subject at university, he said, but a long-time interest. I invited him over for dinner and for discussion with the kids.

Over pasta, I told him I was confused about Mesopotamia, Assyria, and Persia. He helped us with the use of our whiteboard in front of which his dinner chair was strategically placed. My budding historian daughter didn’t enter the conversation, but the value in her seeing that the subject is meaningful for two adult believers is not to be underestimated.

2. Play with Timelines

A timeline is a precise thing, granted. But when we give no margin for error in our Timeline Book, it tends to come across as an object of the parent’s obsessive exactitude, rather than the child’s learning project.

Here are some activities to help budding historians interact with their timelines and consider it their own.

- Write three recently learned facts on the whiteboard such as “Alexander the Great conquered Egypt.” Ask them to scribble a different color on a page for each ancient civilization, where the upper page is the earliest times, and the bottom is later times. You might, for example, notice the colors for both Egypt and Greece stopping as Rome continues, but there is no need for precision at this point.

- Lay a card for each century on the floor, spanning across two rooms. Mark out two events in world history: say, the establishment of Rome and the battle of Hastings. Make up an action for each event, like the wolf of the myth of Romulus and Remus, and the clutching of the eye as in Harold II. Send them to each place on the timeline by calling out either date, the name of the event, or by modelling the action. Every day that you play, add an event and start bustling around with them.

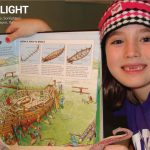

- Ask them to trace an illustrated timeline using tracing paper. Because the activity requires very little higher cognition, my daughter can trace while listening to a book. She can start familiarizing herself with the span of Egypt’s Pharaohs by tracing a little timeline in The Usborne Book of World History along with her favorite of the illustrations while listening to a description of one of their religious taboos in God King.

3. Play Index Bingo

Pick a common subject, like Greek mythology, and create a bingo card for every player. On the cards, write six categories, such as “A book beginning with T,” or “A book with grey on the cover.” The game is to find the subject of Greek mythology somewhere in books that fit the respective categories.

Budding historians will need to know how to use the index for most of these. The first player to find Egypt for all six categories (or for a row) wins. If you lack the relevant material for a subject, try playing at the library.

4. Perform Everything

Don’t let formal learning push out role play and acting out. The brain maps information onto our physical context. Let’s build a little creative world onto which history facts from our History / Bible / Literature curriculum can be projected like a theater. Budding historians can watch the projection back as they recall the dramas they took part in.

- If you read about the myth of Romulus and Remus, act out the establishment of Rome.

- Make a Roman road with LEGO.

- Put a child in his castle-couch and ask for his taxes.

- Construct Harriet Tubman’s freedom train.

- Paint a crusader shield.

- Write a script for a little drama based on quotes from Julius Caesar.

5. Structure the Questions You Ask

I have noticed that the students who care least about history are the ones who cannot see the shape of history. Instead they see an amorphous stream of historical factoids. I want to make sure that my budding history enthusiast is not just running into a lucky crop of appealing factoids, especially when she gets to high school. I want her to see a coherent structure that will outlive her current interests.

1. Genre

Herodatus tells a flawed history. Homer tells a fireside fiction that made history. The Bible tells true history with true poetry. Tolkein uses the tools of these ancient genres to get at something underneath history. The skill of connecting and distinguishing these not only builds a memorable big picture, but actually amounts to the skill of distinguishing truth in general.

2. Bad History

Not all historical accounts are created equal. Some are more significant and some yield more truth. Watch out for when a writer has a vested interest in his own story or for when he is the only source.

3. History That Matters

History is fun, but that’s not why we study it. There is one historical question in particular that is a matter of life and death: Who was Jesus? If our time with Sonlight literature does nothing but build the type of mind that can answer that question truthfully, it will all be worth it.

I want my budding historian to flower into a truth-teller. I want her to serve the world with her discoveries, not just consume factoids. It all starts with the kind of experimentation and play that will help her connect the dots and to hear the ring of truth.

Historical knowledge like this is very important for all of us so that we do not forget the roots and events in the past. There are many interesting things from the past that we can learn.

Exactly why it's important to learn history from a literature perspective! We learn more than names and dates. It's as if we are immersed in that time period.