How do you teach your children the difference between fact and opinion? It seems most schools do so in a disturbing way. It looks innocent enough, but the results are a bit scary.

Read this description from the Common Core:

Facts are statements that can be proven true. Opinions are statements that reflect the author's feelings or views, and they cannot be proved true.

Do you see the problem? Philosopher Justin McBrayer explains it brilliantly in his New York Times piece: Why Our Children Don't Think There Are Moral Facts.

The Trickiness with Facts

Even before Common Core, most children have been taught since their early years in school that facts are things that we can prove true, and opinions are things we merely believe. That's well and good for factual statements like "Ants have six legs," and opinions such as "I think chocolate ice cream is the best." But what about statements like "You should stop at stop signs"? Or even "God exists"? You cannot use the scientific method to prove either of those statements true or false. Yet either God exists or God doesn't exist. Whether I happen to believe God exists does not change the reality.

And there's the trickiness with facts. I would define a fact as "something that is true." We can prove some things that are true, and some things are true even though we can't prove them. Likewise, some of our opinions are true, some are probably false, and some are neither. (There probably isn't a definitive truth on which ice cream flavor is the best, for example.)

I highly suggest you read McBrayer's approachable article to get the full picture. He explains the problem well:

Things can be true even if no one can prove them. For example, it could be true that there is life elsewhere in the universe even though no one can prove it. Conversely, many of the things we once "proved" turned out to be false. For example, many people once thought that the earth was flat.

It's a mistake to confuse truth (a feature of the world) with proof (a feature of our mental lives).

Fact or Opinion? Or Both?

Another problem McBrayer points out? Students learn that statements must be either opinion or fact. But in reality a statement can be both. After his second-grade son dutifully learned at school that a fact is something that is true and opinion is something someone believes, McBrayer describes this conversation between them:

Me: "I believe that George Washington was the first president. Is that a fact or an opinion?"

Him: "It's a fact."

Me: "But I believe it, and you said that what someone believes is an opinion."

Him: "Yeah, but it's true."

Me: "So it's both a fact and an opinion?"

The blank stare on his face said it all.

What this confusion leads to is students' unexamined assumption that all statements of value and morality are simply opinions. Is it wrong to cheat on tests? Should students respect people who are different? Is it OK to kill someone we don't like? Since we can't use the scientific method to find answers to those questions, students assume there are no answers.

There is a Truth Behind Moral Statements

Anecdotally, it seems that most students who enter college today would claim to be moral relativists (saying that there are no moral facts). But did you know most philosophy professors are not? Even in that largely liberal academic field, philosophers know that moral relativism is just not an intellectually tenable position.

Instead of hoping a good professor corrects this intellectual laziness in our students later on, let's teach them correctly from the start. Let's teach our children that things we believe can also be facts. There is a truth behind moral statements. As McBrayer puts it:

Facts are things that are true. Opinions are things we believe. Some of our beliefs are true. Others are not. Some of our beliefs are backed by evidence. Others are not. Value claims [e.g., statements of right and wrong] are like any other claims: either true or false, evidenced or not.

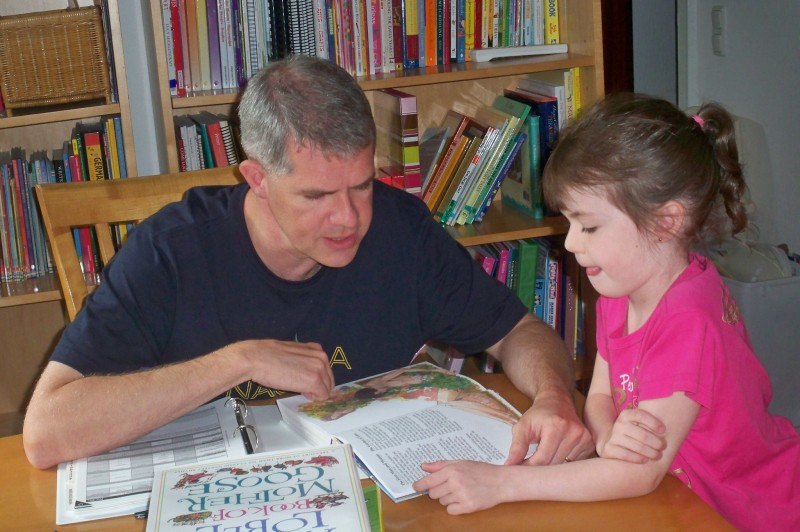

Again, another great freedom of homeschooling! With a literature-rich curriculum that inspires questions and conversations, we can teach our children sound and logical thinking from the beginning. And we can set them up to understand that things can be true even if we can't prove them with the scientific method. Amen!

I like the fact, opinion or both strategy! I was not taught both and it's true often things can be both.

I agree with McBrayer's criticism of the associating of "fact" with "proof". But I think he's wrong to say "Opinions are things we believe."

I would say that an opinion is something inherently subjective and personal. Thus, "George Washington was the first president" is either fact or falsehood; there's no opinion there, and it doesn't become an opinion just because someone believes it. Here's an opinion: "George Washington was the best president."

Even so, I think there's a gray area between fact and opinion. "The law requires drivers to stop at a red light" is certainly fact. But how about "People should obey the law"? Before you answer, imagine yourself rushing a critically injured child to the hospital at 3 AM, on empty streets. Would you obediently wait for the light to turn green? Or what if the law required a mother to leave her physically deformed baby outside to die?

I think McBrayer is oversimplifying when he says "Value claims are like any other claims: either true or false, evidenced or not." No doubt there's a lot of evidence to indicate that murder is harmful to society. It's pretty clear-cut; if we think think of fact and opinion as a sliding scale, we can surely put "Murder is wrong" just a hair shy of the fact end of the scale. But it's not (quite) a fact on the same level as "George Washington was the first president." That's absolutely cut-and-dry; either the dude was the first president of the United States, or he wasn't. But as the Trayvon Martin case in Florida shows, even to say what is murder and what isn't is not always easy. (Was it murder or self-defence? Maybe some of both?) It's not a simple matter of black or white, true or false, fact or opinion.

Is it wrong to cheat on tests? Or to say something unkind to another person? Or to break the law? In the vast majority of cases, yes. Is it always, unequivocally, without a single exception, absolutely flat-out dog-boggered wrong, despicable, and loathesome? No way.

Unproven opinions are not facts. "We should stop at stop signs" is a fact- it is the recorded law and you can be punished for not doing so and cause an accident. As for which flavor ice cream is best, there is no one best. Is there other life in the universe? We do not accept it as a fact until we have proof that there is. Is there a god? Not until it is proven by undeniable proof, not just from someone's belief in old myths or how they "feel" like they have a relationship with their imaginary sky daddy. In educating our family, we do not teach myths as truth but as myths. To do otherwise would be miseducation.

I was taught in school in the 90's that a fact is a statement which can be proven (or disproven) and an opinion cannot. There are false facts. "The sky is green" is a fact. "The sky is lovely" is an opinion.